The structure of Iranian medieval thought was changed by passing through different places for a long time. However, the nature of thought did not change, and so it is the fixed and relatively stable characteristics of these streams of thought that lead historians to analyze the processes of change.

In examining similar structures and functions, researchers of human sciences examine the streams of thought by using the science of structure. The thought of Iranian mysticism born in Khurasan developed by Bayazid Bastami (d. 874) and his followers like Abolhassan Kharaqani (d. 1034) in Qumes and then Sheikh Zahed Gilani (d. 1301) in Gilan and Lahijan.

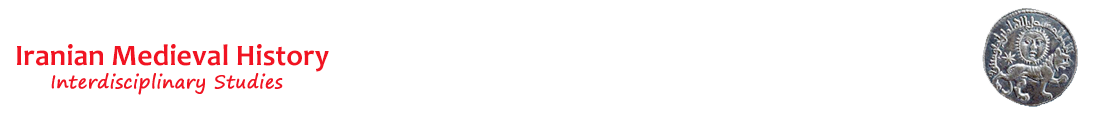

Similarities in structures and functions of social monuments like the mausoleums of Susis in regions with varying climates led historians to find common points among different trends of thought, despite all the challenges they had been through. Similarities in structures and functions of the mausoleums of Bayazid Bastami in Bastam (Shahrud) and Sheikh Zahid Gilani in Lahijan attract the attention of researchers to common points in streams of mystic thought. Even though Sheikh Zahid was buried in a rainy, humid region like Lahijan. This is completely different from Bastam with its climate of four seasons. However, the structures of these two mausoleums have many similarities. The smooth blue dome of the Bayazid mausoleum turns into the multi-angle blue-green dome of Sheikh’s mausoleum.

Living in Bastam, Bayazid was influenced by Khurasan mysticism, while Sheikh Zahid lived in Lahijan and developed mysticism in other cities like Ardebil. Locating two tombs in each of these two mausoleums is the main common function of these two monuments, which distinguishes them from other Sufi mausoleums. Using two tombs from each mausoleum, this article addresses the challenges that mysticism, Shia, and Sunnis went through in the 8th to 13th centuries.

The Mausoleum of Bayazid consists of an interior hall and a large courtyard. Muhammad ibn Jafar (the son of the 6th Shiite Imam) is enshrined in the interior hall (Miraqaie, 2000, p. 48) while the tomb of Bayazid is located in the courtyard in a small metal room. Pilgrims have to step on one stair and bend through a small door to sit down and visit Bayazid’s tomb. The proximity of two tombs representing mysticism and Shia thought has provoked many arguments among researchers.

Bayazid Bastami (d.874) was born in a Zoroastrian family converted to Islam. It is attributed to him by many Sufi orders like Tifuria Naqshbandia and well-known Sufis like Abolhassan Kharaghani and Seyed Heidar Amoli (Alikhani, 2005, p. 14).

Mysticism and its relationship with Shia and Sunni sects provoked many discussions. Considering the existence of two Bayazids in the medieval ages-one living in the 8th and the other in the 9th centuries-, Zaryab Khoie concludes that Bayazid Bstami was a Shiite disciple of Imam Sadeq (Zaryab Khoie, 1995, Shams, 2013, p. 165; Sahlegi, 2005, pp. 63, 93, 94, 128, 133, 179, 181). Some researchers believe that Bayazid and Imam Jafar ibn Sadegh visited each other (Shafi’e Kadkani, 1991, p. 27) and others reject it (Haqiqat, 1966, p. 713).

Bastami was accused of heterodoxy by both Shia and Sunni scholars (Ibn Jozi, 1989, pp. 141-2; 238-241; Muhammad Taher Qomi, 1973, pp. 225-6 Purjavadi, 1999, pp. 14-15; Haqiqat, p. 713). However, there were many scholars like Khwaja Nasir al-Din Tusi (1923, pp. 158-159), Heidar Amoli (1968, pp. 204-206), Ibn Abi Jomhur Ahsaie and Molla Hossein Kashefi Va’ez (1911 pp. 165-166), and Molla Sadra Shirazi (Asfar, 1839, v. 8, pp. 310-311; Al-Shavahid, 2003, p. 220, Mafatih Al-Qayb, 2005, p. 529, Arshiya, 2012, p. 252) who regarded Bayazid as a pious man.

Locating two tombs in Sheikh Zahid’s mausoleum leads the mind from Bastam to Lahijan. It was constructed by Sultan Heidar on a hill to be protected from flood (Rabino, 1839, pp. 364-365).

Consisting of two rooms, the mausoleum of Sheikh Zahid is surrounded by porches. The building is constructed from wood and stone with a ceramic roof (Purahmadi, 2010, p. 84). The shrine of Sheikh Zahid is located in the backroom, and the tomb is hidden in thick green jars. The lack of visibility has created a kind of isolation for Sheikh Zahid’s tomb, similar to that of Bayazid Bastami’s. The tomb of Aqa Seyed Razi ibn Mahdi Hosseini Bashkojaies located in the first room resembles the tomb of Muhammad ibn Jafar in Bayazid’s mausoleum.

There have been many arguments about Sheikh Zahid and his relationship to Shia and Sunni thoughts. He was born in Siyavroud in 1218 (Ibn Bazzaz, 1996, p. 184; Khwandmir, 2008, p. 13; Satipour, 2010, p. 236). Ibn Bazzaz indicates the first journey of Sheikh Zahid to Gashtasfi (Ibn Bazzaz, p. 195). The influence of Sheikh Zahid increased in that region so that the ruler of Sharvan and Qalandars (a group of Radical Sufis) turned against him (Muvahhid, 2002, pp. 188-189).

Sufis generally conveyed their thoughts via oral media, so there are not many documents about their ideas and their relationships with Shia and Sunni sects. The oral tradition followed seriously by Bayazid (Alikhani, 2005, p.14; Haqiqat) and Sheikh Zahid (Movahhed, p. 187) connected Bastam to Lahijan.

We can learn more about streams of thought and their origins by examining the architecture of Bayazid and Sheikh Zahid’s mausoleums. Mysticism is one of the main medieval streams of thought challenged by the Shia and Sunni sects. This paper is not concerned with the Shia or Sunni attribution of Bayazid and Sheikh Zahid, but indicates the coexistence of mysticism with other sects. The proximity of Muhammad ibn Jafar and Bayazid Bastami’s tombs, a long with Seyed Razi ibn and Sheikh Zahid’s, shows how mysticism, Shia, and Sunni applied legitimacy and popularity survive despite all differences. Growth of Mysticism in the medieval time worried rulers about the structure of their powers and so Sufis were sometimes suppressed; however, the capacities of architecture enabled mysticism to show visitors the coexistence of Sufism, Shia, and Sunni thoughts in some periods of medieval times.

Maryam Kamali

References

Ibn Bazzaz Ardebili, Darvish Tavakoli (1996), Safvat al-Safa, ed. by Qolamreza Majd, Tehran: Zaryab.

Alikhani, Esmai’il, Sahib Shathiyat, Kheradname-ye Hamshahri, 2005, n. 69, p. 14.

Rabinio (1947), Velayat-e Dar al-Marz Iran: Gilan.

Purahmadi, Mojtaba (2010). Hendesa dar Gonbad-e Aramgah-e Sheikh Zahid Gilani, Honarha-ye Ziba, n. 43, pp. 83-93.

Miraqaie, Seyed Hadi, Bozorgan-e Gomnam dar Javar-e Bayazid Bastami, Keihan Farhangi, 2000, n. 163, pp. 48-50.

Muvahhed, Samad (2002). Safi al-Din Ardebili, Tehran: Tarh-e No.

Shormij, Muhammad (2011). Sheikh Zahid Gilani va Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardebili az Manzar-e Motun-e Tarikhi, n. 87, pp. 106-89.

Ibn Abi Jomhur Ahsaie (1911). Al-Mojeli, Tehran.

Nasir al-Din Tousi, Muhammad (1942), Osaf al-Ashraf, Tehran: Zavvar.

Heidar Amoli (1968). Jama’ al-Asrar wa Manaba’ Al-Anvar, ed. by Henri Korban

wa Osman Esma’il Yahya, Tehran:…

Qomi, Muhammad Tahir ibn Muhammad Hossein (1990). Tohfat al-Akhyar, Qum: Ketabfori Tabatabayi.

Ibn Jozi, Abolfaraj (1989). tr. Alireza Zekavati Qaragouzlu, Tehran: Nashr-e Daneshgah.

Purjavadi, Nasrollah (1999). Hallaj wa Bayazid Bastami az Nazar Molla Sadra, Nashr Danesh, n. 3, pp. 14-24.

Shafi’ie Kadkani, Muhammad Reza (1991). Musiqi-ye She’r, Tehran: Agah.

Haqiqat, Abdolrafi’ (1966). Bayazid Bastami, n. 139, pp. 712-721.

Sahlegi, Muhammad ibn Ali (2005). Daftar-e Roshanayi, tr. Muhammad Reza Shafi’ie Kadkani, Tehran: Sokhan.

Shams, Muhammad Javad (2012). Ta’amoli dar Peivand Bastami ba Emam Ja’far Sadeq, Adyan, n. 13, pp. 147-171.

MirAqaie, Seyed Hadi (2000). Bozorgan-e Gomnam dar Javar-e Bayazid Bastami. Keihan Farhangi, n. 163, pp. 48-50.

Zaryab Khoie, Abbas (1995). Bayazid Bastami, Daneshnamaya Jahan-e Eslam, Tehran: Dayerat al-Ma’aref Eslami.

Sadr al-Din Shirazi, Muhammad ibn Ebrahim (1839). Al-Asfar al-Arba’a, Al-Hekmat al-Mota’aliya, Manuscripts, n. 2527.

….(2003). Al-Shavadid al-Robubiya fi al-Menhaj al-Solukiya, ed. Mustafa Mohaqeq Damad, Tehran: Sadra.

…2005, Mafatih al-Qayb, tr. Muhammad Khwajavi, Tehran: Mola.

…(2012). Arshiya, tr. Muhammad Khajavi, Tehran: Mola.