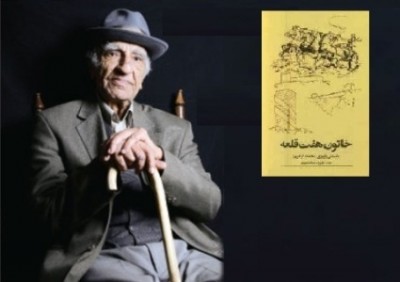

To find the origin of the word doḵtar in many monuments including towers, castles, and minarets we go to “Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a” (the lady of seven castles) of Dr. Muhammad Ebrahim Bastani Parizi has provided the most plausible answer to this question.

“Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a” includes many articles like “Nādar-e dorān” “to take a lesson from Ᾱl-e Mozafar”, “Māria”, “ to fight with corruption” “innocent sinners”, “a tulip of plain” “ trace of women in Qādesia” “from Rāhbar to Golestān Palace”, “dorre-ye Nādere”, “to refresh” (ostokhān sabok kardan). “Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a” (castles and other doḵtar buildings of Iran) in more than 250 pages is the ninth article of this book.

One of the characteristics of Bastani’s historical works is their grandiose titles tinged with fantasy. Undoubtedly, imagination is one of the means Bastani applies to narrate the dark angels of history; however, all his narrations and analyses are based on reliable resources and documents.

Proposing relevant questions to attract his readers is one of the features of Bastani Parizi’s historiography. He is not the claimant of applying interdisciplinary approaches; however, he employs them in “Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a” as in many other articles to provide an inclusive answer to his questions. He applies two sciences of linguistics and architecture to discover unknown aspects of social history.

Bastani applies an inductive approach, attracting the attention of readers. Specifying that “moral and spiritual manners, as well as traditions, have critical impacts on naming certain monuments” (250) Bastani explores the roots of word doḵtar in different monuments including castles, bridges, shrines, and temples. His dynamic and fluid mind takes readers to all parts of Iran in ancient and medieval times. Therefore, readers are required to follow him up in every direction in order not to lose in the amazing world of numerous known names now changed into fundamental questions.

To answer his question, Bastani takes readers to all parts of Iran in medieval times, from Transoxiana to Greece in the Mediterranean area (166). Bringing numerous examples of the word doḵtar in social buildings amazes readers in such a way that Chehel Doḵtar tower in Damghan changes into a single example among myriad historical buildings named with doḵtar, its derivations, and equivalents. Towers of Doḵtar Širāz (151), Bāku (152), Ḵurāsān (152), Miyāna (153), Arāq (153), Šuštar, ḵānaman in Kermān, Šahrestānak, Qom and Nāyin (154), bridges of Miyāna, Koru Doḵtar Lorestn (172), Behbahān (173), districts of Rayy (173), spring of Kāzerun, Bibidoḵtar shrines in Lār, Dome of Chehel doḵtar Kāšan (175), Buḵara (176) and Yazd (178) are just some examples brought in Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a. Regarding his great interest in Kerman Bastani has dedicated a more detailed chapter to the tower of Kermān (156-164).

Bibi (181-182), Nane (205-282), Bānu (210 & 243-251), Mār and Mādar (251-259), Dāye and Māmā (259-261), ḵāhar (263-264), Zan and Pirzan (264-280), proper names like Širin (280-282), Soleimān and Belqeis (261-263), Nāhid and Ᾱnāhitā (283-291) are some other words studied by Batani. Moreover, equivalents of doḵtar in Kordi (186-187), Durhā in Baḵtiāri (187-188), dade in Luri (188-189), Lāku in Gilak (192), ḵātun in Turkish (193) accents are examined.

The critical exact question proposed by the historian about the origin of doḵtar in many Iranian monuments is the thin string connecting all parts of the article. After applying inductive approaches to provide readers with numerous pieces of evidence, Bastani employs a deductive approach, to find the common characteristics of these buildings as follows:

- 1.Being on mountains, 2. Having been constructed in pre-Islamic times, especially in the Sassanian era, 3. Having scared features (194).

Regarding these common features, Bastani proposes his plausible hypothesis that the word doḵtar and its derivations or equivalents refer to Ᾱnāhitā and feminine aspects of ancient Iranian religion prior to the advent of Zoroaster. Nāhid or Ᾱnāhitā associated with fertility, healing, and wisdom is a “tall beautiful woman… with goodness, courage, and purity ( 196). She is the angel of water” “Four elements of earth, air, fire, and water are the religious principles of Iranian people. Special Izad and angels, like the angel of water, protected these elements” (194). His hypothesis is founded on linguistics and Iranian mythology.

Social history addressed in Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a is one of the main concerns of Bastani Parizi. Bastani regards history not as pre-Islamic and Islamic eras, but as connected tunnels through which currents of circumstances flow. It seems that this is the historical continuity that leads Bastani to social history. By the word doḵtar and its derivations, his dynamic mind flows from the medieval era to the ancient time to rest in Ᾱnāhitā temple.

In Bastani’s viewpoint, social history is not limited to ordinary people but is also shared by political agents. The Iranian ancient kings highly honored Nāhid and constructed many Ᾱnāhitā temples. The Šuš temple constructed by Ardešir II (404-359 BC) and the Cyrus tomb in Pāsārgād are specified as two examples of the Iranian king’s attention to Ᾱnāhitā (191).

Ᾱnāhitā was honored not only by women and girls (214) but also by men who felt relaxed under “her strong gentle arms” (191). Dr. Bastani chose to be buried not in Kerman or beside his educated friends in Qet’e-ye Honarmandan, but with his wife, whom he always respected. It can be claimed that “there is always a trace of a woman” (Bastani Parizi, 2001, 218-219& 330-331) in Bastani’s life and death.

Bastani Parizi, Muhammad Ebrahim (1989). Ḵātun-e Haftqal’a, Majmu’a Maqālat-e Tāriḵi, Tehran: Ruzbahan.

Idem (2001). Mār dar Botkade, Tehran: Elm.

Maryam Kamali