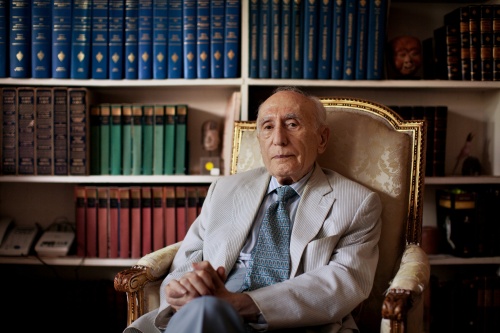

Dr. Ehsan Yarshater (1920-2018), whose name is associated with the Iranica Encyclopedia and The Book Translation and Publishing Foundation, is one of the most prominent intellectuals of our time. He dedicated his life to Iranian culture and literature. On this website, we are to appreciate his work and contributions to Iranian studies. This appreciation includes six articles in memory of his unreserved service to Iranian culture. In the first article, which is now available to readers, we will introduce his works and contributions to Iranian studies and the Persian language. The five articles that will be published monthly, we will include the entries that I had written for the Iranica encyclopedia, but due to Professor Yarshater’s death and the interruption of the Iranica, these entries did not have the opportunity to be released, therefore, they will be available on this website for the first time. These entries are on Damghan’s Chehel Dokhtar Tower, Tarikhana, Sirat-e Jalal al-Din Mengoberni, Seljuqnama by Zahir al-Din Neishaburi, and Takesh-e Khwarazmshah. Also, the link to two other entries, namely, Majdol Eslam Kermani and Mo’ayyed Ay-Abe, which were published in Iranica Encyclopedia during Dr. Yarshater’s lifetime, will be provided to the readers.

Dr. Ehsan Yarshater studied and worked on Iranian culture and the Persian language in Iran and the English-speaking world, including England and the USA. Yarshater was a professor of Persian language and ancient Iranian culture at Tehran University and Iranian studies at Columbia University. He founded the Iranica Encyclopedia and the Book Translation and Publishing Foundation. In addition, he founded the journal Rahnema-ye Ketab (Book Guide) and collaborated with major magazines such as Sokhan and. Yarshater received his PhD degree in Persian language and literature from Tehran University under Dr. Ali Asghar Hekmat. He also received his degree in Persian Language from the Department of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. Yarshater dedicated the collection of these experiences and learnings to one goal: to elevate and enrich the Persian language and introduce Iran’s culture and civilization.

Ehsan Yarshater was born in Hamedan in 1920. The year 1919 is one of the turning points in Iran’s history. Despite not being colonized, Iran was greatly damaged by Russia and England’s great competition, and its resources and funds were captured by them. The 1919 agreement, which made Iran a British colony, was one of the most shameful of these agreements. It was in this year that Reza Shah (1878-1944) entered the political scene with the title of Sardar Sepah to nullify the 1919 agreement and save Iran from falling into the hands of the British Government. Reza Shah’s entry into politics opened a bright window into Iran’s history. A window that put talented and capable people like Ehsan Yarshater on the path to serving Iran and its culture.

Ehsan was born into a Baha’i family. He completed his primary school education in Hamedan, his hometown, and Kermanshah. He moved to Tehran with his family. Yarshater studied at Tarbiat High School established by the Baha'is, and from 8th grade went to Sharaf School. The early death of his mother and father brought about untimely changes. The guardianship of him and his other brothers and sisters was divided between the paternal and maternal family. Ehsan’s share was living with his uncle’s family. The loss of his mother and father could have prevented him from studying. However, with perseverance, he succeeded in the preliminary university exams and was accepted to Tehran University with a scholarship.

The establishment of Tehran University as the first university in Iran and one of the lasting legacies of Reza Shah Pahlavi’s era put Ehsan Yarshater’s academic life and later work on a right track. The establishment of this university in 1934 was the beginning of modern education for undergraduate and graduate studies. Dr. Yarshater was among the first to study at Tehran University, the mother of Iranian universities. The presence of various humanities majors, including Persian literature and linguistics, in undergraduate and graduate studies, and the importance given to these disciplines attracted sharp and alert minds to these majors. This progress that talented people were not all attracted to experimental and mathematical sciences, but could pay attention to the humanities is one of Reza Shah’s main achievements. Ehsan Yarshater was one of those talents.

Yarshater studied Persian language and literature in the Department of Literature and Humanities and received a bachelor’s degree in 1941. At this time, Iran had undergone many changes due to the Second World War. Even though Iran declared neutrality in this war, it was again occupied by allied forces. By violating Iran's neutrality, the Allies attacked Iran from the north and south to deliver troops and equipment to the Soviet Union. In order for the country not to be hostile to the British who were hostile to Reza Shah, Reza Shah resigned in favor of his son and Iran's crown prince, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878-1944), and left Iran. Dr. Yarshater enumerates Reza Shah’s contributions to Iranian culture:

"Reza Shah was a wonderful manager. He really wanted to do something for Iran and succeeded. No king in Iran’s history, perhaps except for Ardeshir I, {the founder of the Sassanid Empire,} could do so much work for his country in sixteen years... In fact, he had created an environment that made all those who wished to serve Iran and hoped their efforts would bear fruit, could gain what they hoped for."

After obtaining his bachelor’s degree, Ehsan Yarshater became a teacher at Tehran Elmiye High School. In 1942, he was appointed vice president of Tehran Preparatory Daneshsara (a training teacher institution). But teaching and executive work did not stop him from continuing his studies. In 1944, he received his second bachelor’s degree in judicial law from Tehran University. Yarshater was accepted in a doctoral program in Persian Literature at Tehran University. Under the supervision of Dr. Ali Asghar Hekmat, who was the Minister of Culture, he worked on his doctoral dissertation entitled "Persian Poetry in the Age of Shahrokh (the 14th Century) or Degeneration in Persian Poetry.” In 1947, Yarshater defended his PhD dissertation and began teaching as an associate professor of Persian language and literature in the Department of Theology, at Tehran University. In the same year, he received a one-year scholarship from the British Cultural Council and was admitted to the Department of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, England, to study and research ancient Iranian languages and history.

In 1952, Dr. Yarshater received a master’s degree from the University of London under Dr. Walter Bruno Henning. In 1960, he defended his thesis entitled “A Grammar of Southern Tati Dialects.”

In 1953 after returning to Iran, Ehsan Yarshater was appointed as an assistant professor of Avesta and Ancient Persian at Tehran University. When Ebrahim Pourdavud retired in 1958, he became a professor of "Ancient Iranian Culture." Yarshater was one of the few scholars who had accurate and correct knowledge of Pahlavi and Avesta and some other languages of ancient Iran. Part of the result of this scholarship is the book “Tales of Ancient Iran,” which won the Iranian royal award for the outstanding book of the year in 1959. Yarshater’s attention to Iran was also based on the literature and history of this country from ancient times to the Middle Ages and from then to his own time. Additionally, among other things, it was important not to fall prey to political games led specifically by left-leaning currents during that period. He tried his most arduous not to be captured by these waves and remain steadfast by focusing on scientific and research work on Iranian culture.

Teaching at the university and educating students interested in Iranian culture and civilization, especially the ancient language and culture, filled a part of his scientific life. However, that was not all Yarshater had in mind. In the same years, he thought of establishing a foundation that could introduce the best works of world literature to the Iranian society. This would increase the Persian language's richness. The establishment of such an enterprise could raise society’s awareness, especially students and young people, about the significant works published worldwide in the humanities, particularly the literature on philosophy and history. This foundation was established with Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi’s support and command in 1954. It was under Yarshater’s supervision. The foundation’s activities gradually expanded so that in addition to foreign literature, collections of Persian writings, Iranian studies, philosophical works, literature for young people, children’s reading books and several other collections were translated and published by the foundation. According to Dr. Yarshater, the Pahlavi government did not have any control over the structure and content of the materials published in this foundation: "The Book Translation and Publishing Foundation was independent in its work, but in terms of its location and name, it was considered one of the Pahlavi Foundations because the initial capital was given by {Mohammad Reza} Shah. We were supposed to report once a year, not to His Highness, but to the Queen {Farah Pahlavi}. This foundation fell into the hands of the Islamic Republic after the 1979 Revolution.”

A significant part of the works published by the book translation and publishing foundation relate to medieval Iran’s history, including Tarikh-e Tabari, Tarikh-e Ibn Khaldoun, Tarikh-e Yaqoubi, Moruj al-Dahab and Ibn Battuta’s Travelogue, all translated from Arabic to Persian. Also, many works in European languages were translated into Persian. Later, in 1986 and when he was in the US, Yarshater resumed Persian texts publication that had been stopped due to the Islamic Revolution. The critical correction of Shahnama ed. by Dr. Jalal Khaleghi Motlaq and the collection of Obeyd Zakani’s poems ed. by Dr. Mohammad Jafar Mahjoub were published.

Dr. Yarshater, besides translating and publishing the world’s most notable works, tried to start an encyclopedia in the Persian language. He explains which kinds of papers were published in 1975 in this book, called Encyclopedia of Iran and Islam: “The translated articles of the Encyclopedia of Islam about Iran to avoid repetition, and secondly, the original articles about Iran before Islam, as well as the articles about the Islamic period. This work was also stopped after the Islamic Republic came to power.”

Yarshater’s interest in introducing the world’s outstanding works to Iranians extended so far that he launched the book guide magazine. A magazine that tried to introduce to the Iranian book-reading community the prestigious works published in the world during that period in various disciplines of the humanities, especially in Iranian studies. This journal was later managed by Iraj Afshar.

Columbia University’s invitation to Dr. Yarshater to teach there was another turning point in his life. Yarshater started teaching at Columbia University as a visiting professor in 1958. In 1961 he became a professor of Iranian studies at Columbia University. The presence of this scholar at Columbia University paved the way for the establishment of the Iranian Studies Center at this university.

Yarshater’s visits to the US and his acquaintance with the cultural works being done at the global level, especially since 1974, made him think of establishing an encyclopedia in English. Yarshater was determined to introduce “Iranian culture to the world as it is.” The establishment of the Iranica Encyclopedia was the result of this significant decision to expose Iranian culture to the world. This encyclopedia provided an opportunity for introducing Iranian culture independent from Islamic culture and not in its shadow: “But I always thought that this encyclopedia [of Islam] has two shortcomings: one is that it does not include Iran’s history before the rise of Islam. And secondly, regarding Iran after Islam’s rise, it did not pay as much attention to Iran as it did to Arabs and Turks.” Dr. Yarshater had the idea of an encyclopedia since the Pahlavi period. Also, prominent researchers such as Saeed Nafisi and Taghizadeh had already proposed it. But Yarshater has sought to create this encyclopedia in English, and if possible, in French, German, and Japanese as well. This extensive work required cooperation with prominent researchers from different countries, including Iran. These researchers worked in different areas related to Iran’s culture, geography, history, and literature. He collaborated with 42 researchers to prepare an initial list of topics to include. Yarshater predicted they could write entries to the prepared list in 40 volumes. This required decades of round-the-clock work and long-term effort.

The preparation of this huge work, which could be a magnificent showcase of Iran's culture and civilization for the world, required many financial resources. With the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, a range of cultural activities in the service of Iran’s culture and civilization faced many challenges. The Islamic Republic not only did not support Iranian studies, but also spent all its efforts fighting against Iranian culture, especially during the Pahlavi period.

However, Yarshater was not afraid of the substantial challenges. Columbia University provided the Iranica Encyclopedia with a small apartment. Yarshater also dedicated all his assets to this project during the time the encyclopedia was being worked on: “In 1990, I established a foundation to support financial aid for the encyclopedia. For some time, Mr. Khosrow Eqbal and Mahmoud Khayyami were the heads of In addition, the National Humanities Foundation of the US provided the cost of this work for some time. Also, holding an exhibition of works of art and antiques for the benefit of the Iranica Encyclopedia was effective to some extent in paying the costs of the encyclopedia.” However, financial issues remained one of Yarshater’s main concerns until his death.

Financial resources were not the only concern of Dr. Yarshater. Finding the most qualified experts to write articles was another of his main challenges. In his conversation, he mentioned that one of the topics he thought about before getting to sleep was who should be included as the author of an entry. Ideally, the author should be the second or foremost expert in the field.

Dr. Yarshater was not stingy in inviting writers and researchers to write entries and invited any researcher who was capable in the fields and topics related to Iran's history. Based on this, unlike many journals that publish articles about Iran while ignoring Iranian researchers, Iranica cooperated with many researchers in Iran. The day I went to see Dr. Yarshater with my husband in 2013, he welcomed us with open arms even though he suffered from hand tremors. When he found out that I had written my master’s thesis on Majdol Eslam Kermani, one of the prominent constitutionalists, he invited me to write an entry on him.[1] Also, since my PhD dissertation was on the historiography of Medieval Iran and social changes related to that period, he asked me to list topics that seemed interesting to me and have not yet been written about in Iranica. One of these entries that was on Moayyed Ay-Abe was published in the Iranica.[2] The other 5 entries were not published because of Dr. Yarshater’s death and interruption in the Iranica’s ativities. These entries will be released on this website monthly.

Dr. Yarshater prepared and published 14 Iranica volumes while alive. In addition, he prepared an eighteen-volume collection of Persian literature history, which was released in 1988. On this website, the 10th volume of this collection, Persian Historiography is introduced.[2] In addition, Dr. Yarshater supervised the translation and editing of many other influential works. Among them, we can mention the translations of Tarikh Tabari and Tarikh Beyhaqi (The History of Beyhaqi). The former work was translated and published in English under Dr. Yarshater’s supervision and editing in 2007.

Yarshater’s scientific and political prejudices were another concern, exposing him to many criticisms. Although Yarshater stressed that Iranica intends to try as much as possible to make the published materials free of bias and based on science, it was definitely not possible to monitor all the materials. Aside from that, the humanities are a field that presents varying opinions and views, and this issue also contains the contents of the Iranica encyclopedia. Yarshater tried to invite all experts to write encyclopedias, however with the establishment of the Islamic Republic and the gap between the younger generation who had studied in Iran and prominent researchers like Yarshater who no longer had the possibility to travel to Iran, this was not always possible.

Ehsan Yarshater wished to finish writing the Iranica encyclopedia as long as he was alive. This wish did not come true, but undoubtedly became a valuable source of introducing Iran’s civilization and culture to the world. He had another wish: "I want even children who grow up in the US to learn Farsi for two reasons: First this preserves their nationality. Second, learning Persian opens a window for them that will be appreciated when they grow up. This {Persian language} is a treasure that one {must} try to get the key to.” Dr. Yarshater’s writings and cultural activities are part of the same valuable heritage today.

Maryam Kamali

Reference

[1]. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/majd-al-eslam-kermani

[2]. Alse see https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/moayyad-ayaba.

Mandana Zandiyan, Conversation with Ehsan Yarshater, Sherkat-e Ketab, 2016.

Bibliography

Theorems and Remarks (al-Isharat wa’l-tanbihat) by Avicenna, tr. into Persian in the 13th century; annotated edition. Tehran, National Monuments Society, 1953.

Five Treaties in Arabic and Persian (Panj Resala) by Ibn Sina, annotated edition. Tehran, National Monuments Society, 1953.

Šeʿr-e fārsi dar ʿahd-e Šāhroḵ yā āḡāz-e enḥeṭāṭ dar šeʿr-e farsi ("Persian Poetry under Shah Rokh: The Second Half of the 15th Century or the beginning of decline in Persian poetry"). Tehran, Tehran University Press, 1955.

Legends of the Epic of Kings (Dastanha-ye Shahnama). Tehran: Iran-American Joint Fund Publications, 1957, 1958, 1964; 2nd ed. 1974, 1982 (awarded a UNESCO prize in 1959).

Old Iranian Myths and Legends (Dastanha-ye Iran-e bastan). Tehran: Iran-American Joint Fund Publications, 1957, 1958, 1964 (Royal Award for the best book of the year, 1959).

With W.B. Henning (eds.). A Locusts Leg: Studies in Honour of S.H. Taqizadeh. London, 1962.

Modern Painting (Naqqashi-e novin). 2 vols. Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1965–66; 2nd printing, 1975.

A Grammar of Southern Tati Dialects, Median Dialect Studies I. The Hague and Paris, Mouton and Co., 1969.

Iran Faces the Seventies (ed.). New York, Praeger Publishers, 1971.

With D. Bishop (eds.). Biruni Symposium. New York, Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University, 1976.

Selected Stories from the Shahnama (Bargozida-ye dastanha-ye Shahnama), Vol. I. Tehran, BTNK, 1974; reprint, Washington, D.C., Iranian Cultural Foundation, 1982.

With David Bivar (eds.). Inscriptions of Eastern Mazandaran, Corpus Inscriptionem Iranicarum. London, Lund and Humphries, 1978.

With Richard Ettinghausen (eds.). Highlights of Persian Art. New York, Bibliotheca Persica, 1982.

Sadeq Hedayat: An Anthology (ed.). New York, Bibliotheca Persica, 1979.

Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. III: Seleucid, Parthian and Sassanian Periods (ed.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Persian Literature (ed.). New York, State University of New York Press, 1988.

History of Al-Tabari: Volumes 1-40 (ed.). New York, State Univ of New York Press, 2007.